The following is a lengthy writeup: a biography on historian Christopher Dawson, his frameworks with Joseph Stuart’s interpretations, his view on culture and history, and why Dawson is applicable today with growing ideological movements and totalitarian governments.

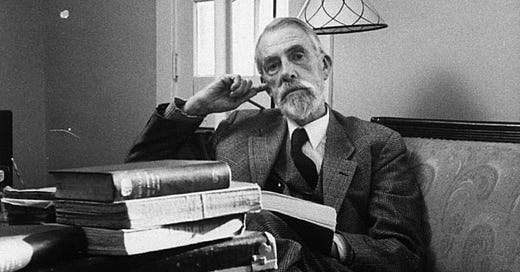

Borrowing the words of Dr. Dermot Quinn, “Christopher Dawson, the great Catholic historian of the last century, has fallen out of favor. Ask the modern undergraduate about him and the response is likely to be a gurgle of incomprehension. Ask the postmodern graduate student and the response will be incomprehension coupled with incomprehensibility…”

Dawson was imaginative. Traditional yet forward-thinking with a serious breadth (and depth) alien to our age of specialization. A “historian’s historian” to one and a “cultural mind” to another, he has written something for everyone, tying the delicate threads of mankind’s journey over millennia. So add Dawson to your reading list—you won't regret it. Begin with the essays in Dynamics of World History, and then onto Progress & Religion, The Age of the Gods, and The Making of Europe.

Christopher Henry Dawson was born on 12 October 1889 at Hay Castle, on the border of England and Wales. He came from a prominent Anglo-Catholic family with a rich heritage that included soldiers, clergymen, and merchants. Henry Philip Dawson, his father, was a Lieutenant Colonel who traveled across the Atlantic to South America and Canada in the 19th century, later inheriting his family’s estate in Yorkshire. Henry Dawson covered Aurora, magnetism, and astronomy, perhaps a prelude to his interest in astrology (“predicting” WW1) as outlined in Edward Watkin’s diary entry:

This global exposure from his father in addition to a massive home library profoundly shaped Christopher Dawson's intellectual curiosity and understanding of the world. Dawson's schooling started at Winchester, one of England's prestigious public schools, but plagued by illness for a year, he instead studied under the Anglican parson to prepare for university. At this time, he met his friend, Edward Watkins—who would also attend Trinity College Oxford—who influenced Dawson’s pilgrimage to Rome. Dawson studied Modern History from 1908 to 1911 at the Trinity College, where he received a 2nd class honors and was greatly influenced by his tutor, Sir Ernest Barker. Recognizing his potential early on, Barker described Christopher as “a man and a scholar of the same sort of quality as Acton and von Hügel.” After Edward Watkin’s conversion to Roman Catholicism, Dawson would make a pilgrimage to Italy in 1909, later falling in love with Valery Mills (a Catholic who described Christopher as a “walking encyclopedia”), and himself eventually convert to Roman Catholicism on Epiphany, 1914, at St. Aloysius in Oxford.

As Dawson was unfit physically for active service, he contributed to the war effort through his work in the Intelligence Division. In the interwar period, he also went to study economics under Karl Gustav Cassel, a Swedish economist and professor at Stockholm University; he later returned to Oxford for postgraduate studies in sociology and history. In 1916, Christopher married Valery Mills, with whom he had three children (Juliana, Philip, and Christina—who would later write Dawson’s biography A Historian and His World in 1991). His marriage and private income allowed him to focus on his research, writing, and lectures. During this period, Dawson began to make his mark with articles for various academic journals, where his writing matured while exploring the relationship between religion and culture. Dawson published his first book, The Age of the Gods, in 1928, at age 40, the culmination of almost two decades of research. He emerged as a respected historian, focusing on the immense influence of religious belief on cultural developments with notable quotes like “a culture can only be understood from within” and “wherever and whenever man has a sense of dependence on external powers which are conceived as mysterious and higher than man’s own, there is religion.” The success of The Age of the Gods led to further publications, such as Progress and Religion (1929) and The Making of Europe, (1932) which expanded on his thesis that religion is the pivotal force behind culture and history.

During World War II, Dawson’s writings grew as he continued to explore the impact of religious and cultural history amidst the backdrop of global conflict (the second mobilization of nations “for the war effort”), expanding onto the threat of a totalitarian state in “mechanizing” society, disruption of the family structure and education, and ongoing secularization. His contributions to journals like the The Dublin Review helped to cement his reputation as a profound thinker (and “bridge” of sorts) in the realms of history and cultural studies; after taking the editorship position for the The Dublin Review in 1940, he allowed for discourse between Catholic writers of all nationalities and political leanings—even allowing conversations between English, French, and German writers through WWII, according to Stuart. In 1947 and 1949, he gave the prestigious Gifford Lectures on “Religion and the Rise of Western Culture” (physicist Niels Bohr presented his “Epistemological Lessons of Studies in Atomic Physics” the year after). In 1958, Dawson’s scholarly achievements were further recognized after his appointment as the first incumbent of the Charles Chauncey Stillman Chair of Roman Catholic Studies at Harvard University. In the appointment of the chair, Harvard’s Board of Overseers wrote “the Stillman Guest Professorship ... will illuminate for future ministers of the Protestant denominations the history, theology, and dogma of the Roman Catholic Church and its implications for the modern mind. In Professor Dawson we have found one whose broad learning and far-reaching sense of the cultural effect of religion in human life make him a respected and admired interpreter of the Roman Catholic Church. Mr. Dawson is the first in what promises to be a notable line of guest Professor” (14 April 1958). Later that September, Dawson taught his first course at Harvard called “Catholicism and the Development of Western Culture.” During his Harvard years, he wrote Movement of World Revolution (1959), The Historic Reality of Christian Culture (1960), Smith History Lecture (1960), Americanization and the Secularization of Modern Culture (1960), and his Harvard lectures were published under "The Dividing of Christendom” (1965), and “The Formation of Christendom” (1967). After four years, though, his tenure at Harvard was unfortunately cut short by one year due to strokes and other health issues, and he returned to England in 1962. Christopher Dawson passed away in 1970 at the age 82.

Dawson’s—the "greatest English-speaking Catholic historian of twentieth century”— keen observations of the historical forces at play and the role of religion in cultural transformations remains relevant in our increasingly ‘multi-cultural world.’ In Dawson’s words, “Every culture has been a religion-culture, that is to say, it has been animated by a religion.” And thus, we must revisit Dawson and the past in attempt to better understand our present and tomorrow.

Despite the ubiquitous use of the term “culture,” Joseph T. Stuart writes, “ it is one of the most complex English words. Few people, even social scientists, agree on its meaning.” (Christopher Dawson: A Cultural Mind in the Age of the Great War, 3). Culture as defined in the Japanese tradition is 文化 [the change of script/Art] adjacent to Nietzsche’s definition: “culture is... unity of artistic style in all the expressions of the life of a people” (David Strauss, the confessor and the writer, 5-6). Writer T.S. Eliot attempts but comes far from a clear meaning in his variegated Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (1949). No explanation is adequate, each merely hinting to an answer—and thus we turn to Christopher Dawson for a concise meaning.

In “The Sources of Culture Change” (1928), he defines culture as “a common way of life—a particular adjustment of man to his natural surroundings and his economic needs.” Extending his idea, Dawson portions the components of culture as follows: genetic (race), geographical (environment), economic, intellectual (psychological, thought, linguistic). The ‘intellectual’ factor is what makes humans ‘human,’ freeing “man from the blind dependence on material environment” and “[rendering] possible the acquisition of a growing capital of social tradition, so that the gains of one generation can be transmitted to the next, and the discoveries of new ideas of an individual can become the common property of the whole society” (The Sources of Culture Change, 5). This intellectual factor is the basis for a culture’s values/morals, expressed through its “religious beliefs, since it is here that they acquire a sacredness which enables them to resist the disintegrating forces at work within a society” (Religion and Culture, 48-50) Culture acts on society as a “bearer of truth,” representing the twin “unity of spiritual and biological elements,” for example, “The more primitive a culture, the more ‘earth bound and socially conditioned’ will its religion appear”). John J. Mulloy, in the afterword of Dynamics of World History, alludes to how Dawson’s idea of the intellectual factor developed, increasingly emphasizing the importance of language as the “most fundamental element in culture... it is the formation and use of a particular language which distinguishes one culture from another” (“The Sources of Culture Change,” 1928). The widening of communication allows a society to further express themselves. Culture, is in fact, alive and organic.

In addition to the definition of culture, the lasting impact of Christopher Dawson’s lies in not only in how he viewed cultures, but also in the way he thought. Joseph T. Stuart’s assess Dawson as a thinker with the following framework: intellectual architecture, boundary thinking, intellectual bridges, and intellectual asceticism. These terms were not referenced by Dawson himself, rather they are implicit, Stuart’s studies uncovering this framework from a careful reading of Dawson’s lectures and writing. Intellectual architecture is an approach to information; laying a foundation for knowledge like a city planner does for a town ensures that every bit of insight is laid out, each essential piece in place like buildings on a main street. This prevents simplifications, necessitating a full analysis and embracement of other perspectives and fields. The next aspect of Dawson’s cultural mind is “boundary thinking” which ensures distinctions remain between various academic disciplines, cultures, visions of reality, spiritual v.s. material etc. Only by understanding differences can one begin to analyze the uniqueness of people, cultures, and disciplines, thus aiding one in understanding how they mix and interact (precursor to later intercultural and interdisciplinary studies)—Dawson’s upbringing on the border of Wales and England led him to value the nuances between people, which is increasingly important today with continued immigration and multiracial families. The third aspect is “bridge building.” Once distinctions/differences between religion and culture, reason and science, psyche and religious experiences are understood, can one link concepts together, “bridging” various disciplines to allow conversation ‘at the table’—bridge building is an active process, not passive. Lastly, and most importantly, is the rule of “intellectual asceticism,” referring to Dawson’s empirical and austere intellectual practice—state the evidence and write within those confines. This is extended with the use of simple, unflattering language free of ideologies (political affiliations, i.e. “left/right,” *READ Destra e sinistra by Norberto Bobbio* etc.) that may detract potential readers. Oftentimes writers’ political ideologies are exposed in their writing, but as Stuart says, one can see Dawson’s conservative sensibilities, but not necessarily his political leanings (right/left) [within his writing]. This careful practice shows restraint and discipline, writing only what is necessary (and not “showing off” his vast knowledge), with a focus on “factual fastidiousness” for communicating ideas.

Next, Dawson’s cultural mind/“theory of culture” further matures with twin approaches to “how” cultures is viewed, either socio-historically or humanistically. The socio-historical view (“descriptive mode”) refers to “how cultures are” while the humanistic view (“prescriptive view”) refers to “how cultures should be.” (Stuart, 8). Dawson is unique as he utilizes both views, studying culture as standalone monoliths (descriptive mode) while addressing the benefits and drawbacks of foreign and domestic cultural practices (prescriptive mode). Acknowledging the uniqueness of various value systems while addressing that cultures coexist in a world together allows Dawson to take nuanced observations of cultures while making broad observations hinting towards the truths within human cultural traditions and civilization. The marriage of Stuart’s four-legged framework with the twin modes of descriptive and prescriptive interpretations creates Dawson’s holistic and multifaceted applied “theory of culture.” Each aspect is a tool, allowing for particular and wide analysis of cultures through their unique languages, geographies (and thus clothing/housing/food choices), technologies, and the change of cultures with assimilations of foreign technology, migration, and more.

The etymology of culture lies with the Latin word “colere” meaning to farm/tend, or to worship—CULTure. The single timeless aspect of history (and humanity) lies within religious traditions. In a secularized “post-modern” society, religion has been overshadowed by mass media and social movements, yet the religious impulse remains—that is human and eternal. As Dawson writes, “Religion is the key of history. We cannot understand the inner form of a society unless we understand its religion. We cannot understand its cultural achievements unless we understand the religious beliefs that lie behind them.” Certain societies may have forgotten the importance and creative role of religion, but that does not negate the existence or significance of religious traditions. Dawson’s writing and cultural framework provides us better guidance on how we came here, where we are, and where we may be headed—hopefully Christopher Dawson’s hindsight can be unlocked and used to strengthen our foresight in the 21st century.

To use Dawson’s insights, one must revisit the time where his idea of culture was formed. The pivotal moment for Dawson lies with World War I, or as historian Simon Schama refers to as ‘the original sin of the 20th century”—the original sin, like Adam and Eve, led to later sins of totalitarianism and dictators like Hitler, Mussolini, and ideological warfare with the Soviet Union and USA. Historically, Europe, or “Western civilization” had four overarching components: Greek thought and art, Roman law and organization, native European [pagan] traditions (Jul, etc.) and kingship, and Christianity spread by missionaries (that pacified us Scandinavians). Each aspect blended with each people’s respective geography and tongue, creating their ‘common way of life’— culture. Though, throughout the 19th century, a phenomenon of reductionist thinking emerged, Hegel reducing humanity’s final aim to an idea of “freedom” (as legislated by a Rechtsstaat), Karl Marx simplifying culture and human behaviors to merely economic/class factors, nationalist historians reducing cultures to race or geography, and more. This "lust for simplification," Stuart writes, washed away all detail and nuance, plaguing Europe, as narratives of nationalism began to shape the minds of historians, diplomats, military leaders, and citizens. Reductionism had become a component of ‘modern’ thought, antithetical to intellectual architecture. Stuart writes "Sociologists reduced culture to external human practices or to internal beliefs, historians reduced it to politics, politicians reduced it to money or class or race, and educationalists reduced it to specialization... A largely one-sided notion of culture reduced human life to either its material or spiritual dimension” (Stuart, 13). The way out, Dawson believed, was through rigorous interdisciplinary studies, analyzing cultures from various subjects. The makeup of a culture’s ideas from the study of its theology, philosophy, linguistics, psychology, its genetic factor through anthropology and sociology, its work factor through studying economics, and the environmental factor through studies of geology, geography, and climate. In the age of specialization, this return is perhaps necessary, valuing deep generalists that have the humility to be interested in other fields, talking to experts, weaving interdisciplinary insights to create a mosaic of world cultures.

In Dawson’s time, the fruits of decades long archaeologic research originating from the antiquarian movements began to show, allowing one to attempt to construct a “general synthesis of the new knowledge of man’s past.” Prior to such research, historians relied on fewer sources, complicating the inductive process. In the 18th century, Sir Richard Colt Hoare wrote, “We [antiquaries] speak from facts, not theory,” changing the trajectory of man’s understanding of man. Dawson’s “The Sources of Cultural Change” attempts to bridge antiquarianism and cultural study, to construct “broad outlines” to witness and understand the “primary foundations on which our civilization has been built up” (3). This is Dawson’s socio-historical analysis (descriptive) of cultures, a way to reveal the shared truths below societies, reminiscent of historian Henri Pirenne’s “if I were an antiquarian, I would have eyes only for old stuff, but I am a historian. Therefore, I love life.” Dawson remains intellectually honest, acknowledging that “there is no lack of gaps in our knowledge”—the heart of history is mystery—but nonetheless, if broad strokes of cultures can be seen, truths of history can be revealed, serving as a counterweight to historical frameworks founded on beliefs of shared race or geography, which tend towards nationalistic ideas and away from unifying frameworks. Dawson describes historical European thought of the 18th and 19th centuries as “almost exclusively national interpretation... so that history has often sunk to the level of political propaganda” (4). His usage of propaganda is peculiar as the [religious] etymology of congregatio de propaganda fide, hints to modern faiths based on “the sacredness of the Fatherland—the consecration of Place” away from a unifying transcendent, towards “religious emotion divorced from religious belief.” (Prevision in Religion, 103). By addressing the core of political propaganda, Dawson seeks to separate history from nationalistic interpretations towards one founded on “cultural or sociological” ones, focusing on the “fundamental social unity” that constructs a culture. As “propaganda becomes ineffective the moment one is aware of it,” seeking broad sketches within cultural studies prevents simplifications, and the tendency towards nationalistic thought. Helen Mears addresses a similar view, writing “in a time of crisis, any tradition—if it is a genuine one—can be used to unify a people behind an aggressive program. Such traditions are not a cause of war. They are appealed to as a technique for achieving national unity behind a war program (called, however, a defense program), once war is decided on by policymakers for other, less esoteric, reasons.” (Mirror for Americans: Japan). By understanding the shared cultural traditions, and how they can be corrupted, perhaps one can look beyond the political unit and understand the true foundations of civilizations—contrast brings clarity.

At the heart of this concept, lies Dawson’s religion (or religious impulses) as a “key to history”; for European civilization, Christianity and places of worship, for Islamic civilization, the Quran and associated traditions, for Japan, the importance of Shinto and the Emperor (“They must have something to worship”), so on and so forth. This “key” is particularly relevant today, as the powerful ideological social movements of the 20th century (Democracy “consecration of Folk,” socialism “consecration of Work,” and nationalism “consecration of Place”) parallel the 21st century’s weaker social movements of European “hyper environmentalism” but contrast the anti-social “identity politics” and “progressive movements”—which are mostly distractions from more pressing issues like stagnation, financial inequality, and the rise of Marxism in the West.

To reiterate, culture is “a common way of life,” how a group of people adapt with their environment and needs to survive and reproduce. Thus, culture is acted upon and acted on— nature influences man, and man (using tools) influences his surroundings, too. Dawson addresses “higher” and “lower” cultures, as ones further or closer to its environment, respectively; he writes, “the [lower] culture the more passive... the higher culture will express itself through its material circumstance, as masterfully and triumphantly as the artist” (4). Of the four aspects of culture (genetic/race, geographical/environment, economic/work, intellectual), the first three are derived from Frédéric Le Play’s Place-Work-Folk (Lieu, Travil, Famille) theme with Dawson contributing the fourth intellectual factor; in Progress and Religion, he writes, “[culture] is neither a purely physical process nor an ideal construction. It is a living whole from its roots in the soil and in the simple instinctive life of the shepherd, the fisherman and husbandman, up to its flowering in the highest achievements of the artists and the philosopher,” combining the biological factors of “the animal life of nutrition and reproduction” with higher elements of “reason and intellect” (45). Le Play’s views on the family as the basis of society derives from local geographies that stages the needs and possibilities of a given people, thus the type of work required to survive; this work (pastoral agriculture, rice production, hunting, fishing, etc.) simultaneously shapes the family structure (different needs for different work), the “biological unit” of society. Later, these simple societies, geographically determined, evolved into complex ones because of migration and technological advancements in tools, boats, and metals.

Dawson’s intellectual factor, and particularly the importance of linguistics, “distinguishes man from the other animals” allowing for expression of ideas, art, and communication overtime (retained through literature, plays, etc.), contributing to the formation of a culture. Like cultures, language, too changes, as seen with simplified and traditional Chinese characters in East Asia. After the People’s Republic took over mainland China, in attempt to modernize and increase literacy, Mao reduced the number of characters and selected for characters with fewer strokes, rather than keep complex characters with depth and nuance. Though script reform has been a part of language development in Asia—particularly with the Meiji government’s push for a standardized Japanese—the Maoist simplification removed characters with rich connotations, reducing cohesion and confining written vocabulary in the mainland. Ironically, the legacy of complex Chinese characters is preserved outside China in Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and parts of Japanese characters. Ideograms, as used in Chinese characters, are foreign to Latin based writing, though increasingly important to understand as “the sum of human wisdom is not contained in any one language, and no single language is capable of expressing all forms and degrees of human comprehension.” (ABC of Reading, 76). As language is the means of communication, it also necessitates a uniformity in the organization of society. As the first step towards a civilized society, Dawson addresses the sort of “discipline” required for a common tongue, writing it “can only be produced by ages of cooperative effort—common thinking as well as common action” (Religion and the Life of Civilizations, 121). In addition to language, the intellectual element that Dawson introduces includes a culture’s art, philosophy, thought, religion, and science, which seeks to “unify the various activities of the group” through a shared morality or “common set of values,” with origins that lie in the religious beliefs of a society. John Mulloy writes, “The maintenance of a society involves both a community of belief (agreed upon values) and a continuous and conscious social discipline... there must be some factor in culture which can command the allegiance of the society’s members against the temptations of an anti-social individualism” (Afterword, 455). This discipline is demonstrated—an act of choice—for the purpose of achieving some social goal. The cooperation of villages to produce grain or rice, to help one another in natural disasters, to defend themselves from adversaries in a unique geography (plains, desert, coastal region, etc.) are all factors which ultimately shape a culture, creating their “different conception of reality, different moral and aesthetic standards, in a word, a different inner world” (Progress and Religion, 76). At the same time, within cultures, there lies a careful balance between the rural and urban, in addition to regional peculiarities under a common way of life. With continued migration from the countryside to city life, there’s been a pattern Dawson identifies where “... cosmopolitanism... produced homogenous cities, homogenous citizens. Urban man, deracinated and de-spiritualized, forgot the sources of his moral vitality: family, region, local clay. As with early civilizations, so with late: the closer to the land the better.” This quote was in relation to widening gaps between Greek rural society and urban classes but remains timely—if the foundations of a culture disappear, the culture will decay, and become replaced (or inherited) by “those populations which live under simpler conditions and preserve the traditional forms of the family” (The Patriarchal Family in History, 173) and land.

Regarding the types of cultural and social change, Dawson outlines fives forms: the development of culture within an isolated environment (no foreign intrusion), when a society enters a new geography, when two societies mix, the adoption of foreign materials (outside innovation), and the introduction of new ideologies. The first, relates to a society living in harmony with their environment, a full adaptation of themselves to the surroundings; Dawson refers to these societies as “precultures,” providing an example of the Eskimos (Inuit and Yupik) in the Arctic, a classic triumph of man over nature. Next, a change Dawson describes relates to the change of environment, where a society originally in the plains meets the coast, or a mountainous people moves to the steppes; he directly mentions “the invasion of India by peoples from the steppes and plateau of Central Asia” (Sources of Cultural Change, 7), emphasizing the differences in climate and its impact on common ways of life. Third, Dawson writes on the most common of cultural change, where two cultures meet, either by peaceful means (from trade) or by conquest. This process alters the culture fundamentally, fusing two differing ways of life and eventually resulting in a stable new culture. This process of cultural exchange takes centuries, where initially the people continue to live on the “older” cultural traditions, followed by a period of “intense cultural activity, when the new forms of life created by the vital union of two different peoples and cultures burst into flower” (8), resulting in new interpretations, art, cuisine, and more. This process is either an old culture being “reborn” because of foreign influence, or the newer culture revitalizing the existing “old culture.” As with any change, this process can lead to violence and conflict, as two cultures attempt to reach some harmony and thus stability. An example lies in the mutual cultural influences between China, Korea, and Japan, which individually influenced each other through cultural exchanges (and war), and migrations between one another. Next, Dawson outlines a cultural change when a society adopts material elements from a different culture; this includes innovations in metals, irrigation techniques for agriculture, to weapons and methods of transportation. Material changes alter cultures as they have the potential to change the domestic social structure. An example lies when an isolated culture (Japan) was introduced to matchlocks by Portuguese traders, fundamentally changing internal feudal conflicts; the Oda and Tokugawa clans were able to have a decisive victory over the Takeda clan, by preventing cavalry charges with volleys of bullets. Within half a century, these weapons were used by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the invasion of Korea (Imjin War) delivering early victories with the combination of traditional bow and arrow with muskets. Though, a key point that Dawson addresses in changes in material culture is the necessity for internal development too, writing “it is remarkable how often such external change leads not to social progress, but to social decay. As a rule, to be progressive change must come from within” (9). Lastly, another form of cultural change lies in the “adoption of new knowledge or beliefs, or to some change in its view of life and its conception of reality” (9). The introduction of ideologies foreign to a society alters their vision of reality. Dawson provides two examples from the 18thand 19th centuries, comparing the industrializing West with the stagnant Islam, writing, “the faith in Progress and in human perfectibility which inspired the thinkers... in Europe, was essentially of this order, just as much as was that great vision of the vanity of human achievement which Mohammad saw in the cave of Mount Hira and which made civilizations and all temporal concerns as meaningless as ‘the beat of a gnat’s wing’” (Sociology and the Theory of Progress, 43). Ideological changes are perhaps the most enduring, as the change in the perception of life drives the culture forward (or backwards); Dawson alludes to the notion that the beginning of civilization, lay in the “man’s fruitful cooperation with the powers of Nature,” beginning in Mesopotamia with agriculture and basic metallurgy, the beginning of writing, law and the development of trade. Next, the vision of reality morphed with “the age of the Hebrew Prophets and the Greek philosophers, of Buddha and Confucius, an age which marks the dawn of a new world” (Sources of Cultural Change, 11). This notion of a new vision of man’s reality remains pertinent today, as humanity’s horizon extends beyond Earth into space, while simultaneously totalitarian ideologies attempt to subvert human dignity through new methods of control.

Returning to Dawson’s formative years, the rise of secularization from compulsory education, mass societies, and the effect of the Great War are all linked to the expansion of the state and the centralization associated with it. In “Sociology as a Science,” he writes that governments are “extending its control over a wider area of social life and is taking over functions formerly regarded as the province of independent social units (family, church)... or voluntary activities of private individuals... it is not merely that the state is becoming more centralized, but that society and culture are becoming politicized” (32). He references how politicians are now addressing issues of birth rates and poverty, when previously the role of the state was for “the preservation of internal order and the defense of the state against its enemies.” (32). Though, perhaps this was the natural response following a war which mobilized the entire society, and the increase in the influence of public opinion on politics. While total war (guerre à outrance) is commonly used in reference to the two World Wars, it predates the 20th century with most aggressor nations/tribes, like the Mongols conquests or with the French revolutionary wars introducing mass conscription; mandatory service necessitated a larger social system to sustain such a war effort. Though, it was the sheer scale of mass mobilization of the Homefront and millions of soldiers that set the Great War apart. Then, a nation’s goal was to survive by any means necessary; as a mechanized society allocated [labor and material] resources most effectively, the production of weapons and goods increased the chance of survival. But as the Homefront became more involved, they too became a target. German commander Peter Strasser’s developed long range bombing (with Zeppelins) to target military and civilian targets, stating “we who strike the enemy where his heart beats have been slandered as 'baby killers' ... Nowadays, there is no such animal as a noncombatant. Modern warfare is total warfare.” The lack of separation between civilian and military targets, brought civil infrastructure and cities into the warzone, affecting the livelihood of woman and children on both sides. Technological innovation brought about new tools and weapons, the introduction of tanks, airplanes, and machine guns changed the vision of reality for European soldiers like Native Americans receiving horses from the Spanish. Dawson writes, “these changes are the work of Western man through the science and technology and the institutions and ideas that he has created or invented. Whether this is good or bad is another question. We still do not know whether this will be the foundation of a new world order or whether Western man, like Frankenstein, has created a monster that will destroy him” (421, Europe in Eclipse). The double-edged sword of innovation; there would be no humans without technology (tools), and yet people are right to fear runaway technology—major innovations after the 19th century has increasingly had a military dimension to it, popping a pin in the idealistic bubble of “Progress.”

In addition, the logic of mobilization and emphasis on efficiency (almost an atheistic Puritanism, productivity as “God”) brought about another change in the vision of reality for Western citizens. Work on Sundays lead to the declining of church attendance, creating a new, backwards image of man. Stuart writes, “the war spread the logic of mobilization that pushed efficiency as the highest value, creating a new ideal of ‘man the worker’ with a mind of metal and wheels, an ideal that eroded the humanistic values of Dawson's time.” (Stuart, 59). Unfortunately, if ‘efficiency’ is established as a rule, “it becomes an inner compulsion and weighs like a sense of sin, simply because no one can ever be efficient enough... And this new sense of sin only contributes further to the enervation of leisure, for the rich as well as the poor” (Art and Culture, Clement Greenberg). The impact of war fundamentally altered life, the interaction between work and leisure, as efficiency was a matter of life or death—unless one outworked the other country in the production of armaments, one was lost. The outcomes of war were often based on the industrial output of a nation, the economy that could provide more weapons, ships, planes had an advantage, a quicker path to victory. Simultaneously, scientists of each nation were tasked with innovations in chemical and biological warfare, introducing deadlier weapons previously banned by the Hague Convention in 1899. British captain John Crombie wrote, “we can only beat Germany by assuming her mentality, by recognizing the State as the Supreme God whose behests as to military efficiency must be obeyed, whether or not they run counter to Christianity and morality. We call their use of gas inhuman, but we have to adopt it ourselves; we think their policy of organizing the individual life contrary to the precepts of freedom, but we have to adopt it ourselves" (Stuart, 61). Similar reasoning returned in World War II, with Francis Fukuyama writing, “the wars unleashed by these totalitarian ideologies were also of a new sort, involving the mass destruction of civilian populations and economic resources... to defend themselves from this threat, liberal democracies were led to adopt military strategies like the bombing of Dresden or Hiroshima that in earlier ages would have been called genocidal” (End of History and the Last Man, 6). Dawson alludes to the necessity for increased and stricter “social discipline” as cultures mature, alluding to the fact that the greater the cultural achievements, there is an increased necessity for “moral effort and the stricter is the social discipline that it demands” (The Patriarchal Family in History, 168). Though writing on the matrilinear versus patriarchal family traditions, this idea coincides with technological advancements, too. As modern technology often has civil and military applications, societies and governments today require greater moral discipline to ensure such powers are not abused and used for evil means.

T.S. Elliot, a writer influenced heavily by Dawson, wrote, “today [common religious traditions and standard of literary culture] have been abandoned by the rulers of the modern State and the planners of modern society... have come to exercise a more complete control over the thought and life of the whole population than the most autocratic and authoritarian powers of the past ever possessed” (Notes towards the definition of culture, 115). Dawson influenced T.S. Eliot’s thought as he matured as a thinker; initially, following in the French counter revolutionary movement Action Française, Eliot followed in the footsteps of Charles Maurras, infamous for the slogan “politique d’abord” or “politics first.” According to Professor Lockerd of the T.S. Eliot Society, Maurras’ influence on him faded as he was introduced to Dawson’s work, as he began to understand the importance of religion in culture. Dawson and Eliot both identified that without a religion, the religious impulse is substituted through deifying the state or race. Dawson writes, “the essential characteristic of National Socialism is to be found rather in its attempt to create an ideology which will be the soul of the new State and which will co-ordinate the new resources of propaganda and mass suggestion in the interest of the national community... It is a new form of natural religion... a mystical neo-paganism which worships the forces of nature and life and the spirit of the race.” The religious impulse is integral to a culture, and the attempts to sunder religion from culture (in the 17th and 18th centuries) merely left an opportunity for political systems to fill a void—which totalitarian regimes gladly took advantage of. Simultaneously, with continued specialization in modernity, it’s as if man is morphing into a smaller cog in a larger, globalized machine, a hypertrophied caricature of Adam Smith’s pin factory. The inability to think about the bigger picture, has perhaps stunted modernity, even with massive amounts of information at our fingertips via new technology like the Internet. Dawson, ruminating on the effects of the Great War wrote, “the average man realize[d] how fragile a thing our civilization is, and how insecure are the foundations on which the elaborate edifice of the modern world-order rests. The delicate mechanism of cosmopolitan industrialism needs peace more than any previous order. If modern civilization has increased enormously in wealth and power, it has also become more vulnerable.” An integrated civilization is in a precarious position due to its accomplishments—which introduces a separate concern on the paradox of globalization, there is a global market but no “global government.”

Returning to the post-modern west, we are faced with similar concerns on totalitarian states from Dawson’s time, yet with surveillance technology and new ideologies adopted from Marxist principles. In the name of “equity,” parts of the West are attempting to redistribute social and cultural capital, on grounds of identity, separated by oppressor/oppressed, and racial grounds. The Dawsonian analysis of religion as the “Key” to History oftentimes explains the movements shaping society and institutions. The inherent flaw in the movements (post-colonial theory, radical feminism, critical race theory, queer theories, Wokeism), is the same as nationalism, communism, from the 20th century—they are not divine, and thus cannot transcend nor unite man. The concept of a transcendent rose as a point of unity (in Judeo-Christian traditions), but the ideologies lacking a transcendent are not "high enough.” As they cannot unite man, they inevitably exclude groups of man, along the lines of race, gender, or political belief. There are countless examples of this in the 20th century, Nazism and the concentration camps, or the Soviet Union and Chinese’s “cultural revolution,” murdering tens of millions of people along the way (Marxism took over in agriculturally driven feudal societies). If one preaches “inclusiveness” or “tolerance,” the best advice is probably to run the other way. Even the term “political correctness,” has its roots in communist ideology, alluding to a card holding member that will hold the party line. The ideas of individual freedom and liberal rights too are not sufficient as a transcendent (“unifying figure”), as the exercise of one’s individual freedoms can create conflict, making an appeal to higher ideas that unite people increasingly difficult—thus, resulting in forms of cultural fragmentation (or even isolation) as seen in America today.

What does the priest, Western militarist, and billionaire capitalist have in common? The three are all anti-communists.1 During the Cold War, anti-communists were not aspiring to control the world, they were united in preventing communists from taking over liberal democracies. Once the Soviet Union fell, this unity from a common enemy disappeared, and in a secularized society, the search for a uniting belief by any means (religious or pseudo religious) continued. To salvage the humanistic and spiritual traditions that build the modern world, one must remember that “the process of secularization arises... from the loss of social interest in the world of faith. It begins the moment men feel that religion is irrelevant to the common way of life and that society as such has nothing to do with the basics of faith” (The Historic Reality of Christian Culture, 19). Parts of the West have begun to realize that the real antidote to ideological subversion lies with faith. The lasting idea from Dawson that the key to history lies in religion is at the heart of today’s political and social interactions, as the basis of liberal values derive from the Christian traditions—one cannot remove the roots of society (faith) and expect fruits to grow from it. Thus, we look to Dawson’s interdisciplinary method of cultural study to stitch together the spiritual and intellectual traditions that build the West, to engage with traditions that built the East, in the pursuit of the preservation and spread of humanity’s shared wisdom for years to come.

Some sources:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1509108?seq=16 Harvard Theological Review

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspl.1883.0092

https://christopherdawson.org.uk/works/

https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/modern-pioneers-christopher-dawson

Christopher Dawson, Culture, and the Spiritual Vacuum of the Modern West (link) Christopher Dawson and the Challenges of Interdisciplinary Studies with Dr. Joseph T. Stuart (link)